Перейти к:

Чувственная ментальность и когнитивно-духовная терапевтическая интервенция

https://doi.org/10.31162/2618-9569-2019-12-4-1091-1106

Аннотация

Целью данного исследования является изучение влияния когнитивно-духовной терапевтической интервенции на повышение духовной направленности участников. Утверждается, что чувственная ментальность – это расстройство личности, которое может привести к потере человеком духовной, эмпатической и мыслительной способности. Выдвигается гипотеза, что при когнитивно-духовном вмешательстве духовная ориентация может быть усилена. Это исследование – эксперимент с констатирующим и контрольным этапами: пре-тестом и пост-тестом. Измерение духовности проводилось с помощью «якорного» личностного опросника. Участники в ходе однодневного семинара работали через когнитивные, аффективные и духовные переживания над жизненными ориентациями. Из 22 участников было 20 участников, заполнивших данные теста до и после эксперимента. Результаты показывают, что духовность значительно возросла среди участников. Средняя предтестовая оценка равна M=1.517, а пост-тестовая составляет м=2.166. Таким образом, средняя разница составляет 0,649, при t-балле = 4,25, р<0,01. Таким образом, когнитивно-духовная терапевтическая интервенция может использоваться для влияния на жизненную ориентацию тех, кто обладает чувственной ментальностью.

Автор заявляет об отсутствии конфликта интересов.

Ключевые слова

Для цитирования:

Рийоно Б. Чувственная ментальность и когнитивно-духовная терапевтическая интервенция. Minbar. Islamic Studies. 2019;12(4):1091-1106. https://doi.org/10.31162/2618-9569-2019-12-4-1091-1106

For citation:

Riyono B. Sensing Mentality and the Cognitive-Spiritual Intervention. Minbar. Islamic Studies. 2019;12(4):1091-1106. https://doi.org/10.31162/2618-9569-2019-12-4-1091-1106

Introduction

In the 70s Alvin Toffler predicted the phenomenon of “future shock” or surprise that will occur in the future, which he called the information age [22, p. 326]. Interestingly, this era is often perceived as an era of progress, many of which boast convenience. Toffler’s term “shock” is not seen as surprising or undesirable. In general, digital native and digital immigrant vying to jump into this information age by creating accounts on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, Line, and all forms of social media. Why do we need to be wary of this era of social media?

Future shock is not only about physical illness, but also a matter of psyche [22]. Toffler asserted that just as environmental overstimulation can harm the body, it brings just as negative effects on the mind. In response to such overstimulation, people experience future shock. There is a term called “sensing culture”, which is originated from Sorokin [20]. Sensing culture can be seen and felt through a new pattern of behaviour, including social media habits. As the name implies, “culture”, these habits become a new culture. Decision-making is based on trending topic, which is popular at the time. Then, there are phenomena of “Insta-famous”, people who enjoy popularity by manipulating followers on Instagram1.

Such phenomena occur within a wide range of life affairs. In the case of crime, for example, there are cases of paedophiles that have social media accounts. This does not make sense because he announces his cruel deeds, something that will help the authority to arrest them. Why do these things happen? Why can human behaviour change like that? Why would anyone post a status on social media before committing suicide?

This “shock” is currently not in the domain of public awareness. In this era, many people have lost their reason. Our life is now filled with social media. This is actually a shocking information revolution. Why does it happen and is it bad? Some people say before social media were created there were already good people and bad people, so this phenomenon is considered normal, there is nothing new or shocking about this. The difference is only that in the past there was no social media so that people were not well informed. However, the focus of the problem is not the existence of social media, but why do people today announce their evil and cruel deeds. Here is why the concept of sensing culture becomes important for us to understand.

This paper tries to see these phenomena from the perspective of psychology as a science of the soul, not just behavioural science because behavioural science cannot explain it. We are all very familiar with the physical and spiritual terms. However, not all people believe in the soul, so the mainstream psychology of science negates the soul. The most sophisticated branch of psychological science today, neuroscience, is even more confident that there is no soul because they can observe brain activity that is physical or material. Thus, the science of the soul itself is not a popular science in the repertoire of modern scholarship. However, actually, in the classical repertoire of psychology, psychology is the science that is concerned about the heart or of the soul [1], while the science of the body is the focus of medical science. If the science of psychology is learned from the body, then it is no different from the science of health. By focusing on the soul psychologists should be able to make a unique contribution to human science.

If we study the classical sciences that flourished in the Middle Ages, there is much discussion of the psyche, especially among Sufism and philosophy. In addition to Muslims, the West was talking about the soul. One of them is Plato. The science of tasawwuf addresses the layers of the soul called nafs. In English or classical repertoire is known as soul and spirit. In the book of Ibn Arabi the soul is divided into seven layers simplified by Imam Ghazali into two. These two types of souls are called human spirit and animal spirit, or in Arabic “nafsuninsaniyah” and “ nafsunheywaniyah”.

Based on the literature study, this study tried to make a frame of the soul layer to understand the phenomenon of sensing culture. Like the soul and body, or body and spirit, are two different entities, the soul is part of the spirit whose symptoms and dynamics we can learn a little. The first phenomenon that shows that the soul is separate from the body is sleep. Sleep is a time when the soul and body separate, so that the body as if dead, while the soul is somewhere. Dreams can be clues, satanic temptations, or just random sleeping experience. The second phenomenon occurs when we are able to feel, imagine, and think of something invisible and not here as if to remember something. However, remembering in this context is not just like the theory of recalling information, but we can actually be there. In fact, we can cry again after remembering a very moving event. Although it has been a long time ago, we still remember it as if we were back in time. The return is certainly not a body, but a soul. Muhammad Iqbal illustrates it as a visit to the Taj Mahal, then when returning home it still feels the impression and beauty of it. Therefore, the soul is beyond or more than physical. From there then came the concept of memory, imagination, and so on which is a component of the soul.

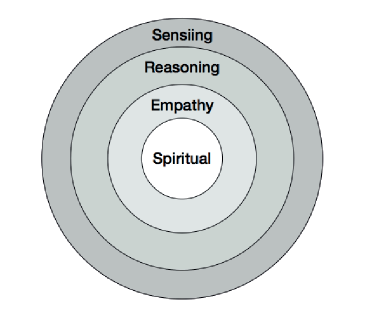

Although soul and body are a different entity, they are related when we are conscious. It shows how we can move our limbs. The outermost layer of the soul is a layer that is directly connected to the body or the five senses. So the outermost layer of the soul is called the sensing layer or sensory layer: sight, hearing, smell, taste, and touch. These outermost layers are attached to our body. While sleeping, our five senses do not work, or may work but are not accurate. This is because our senses are separated from the body. For example, a person who is sleepwalking does not realize that he is walking.

The deeper layer of sensing is the reasoning layer. Often people call it the brain. However, in this Islamic concept also involves the heart. Reasoning is a process of what is felt by the sensing, so that when we reach the reasoning level we can understand what is happening. In this layer, we begin to ask, “Why does this happen? What’s the point?” On the other hand, sensing does not raise questions, we just enjoy or accept what we feel. In this case for example aromatherapy, massage, melodious sound, and noise. These things can bring benefits or disrupt. So sensing is something that is also very meaningful but only temporary and superficial, not deep enough.

Sensing is the connection between soul and body, is peripheral. Reasoning is the connection between the soul and the phenomenon that occurs. Meanwhile, the third layer called the empathy layer is the connection between the soul and other human souls. Transpersonal psychology, one of the streams of psychology that begins to study the science of the soul, claims that the connections between human souls can be understood with this flow. In layers of empathy comes feelings such as love, affection, longing, and compassion. For example, love cannot be logic because logic lies in reasoning. Beautiful women have a partner who is not physically attractive, the one who sees cannot see the love between the two, but who has that soul can, due to connection with other souls.

The deepest layer is called the spiritual layer, the connection between man and God. This is much less noticeable than the empathy layers. The indicators are difficult. People who diligently pray are not necessarily actually spiritual if the intention is “riya” (showing off). “Ikhlas” (sincerity) and “ihsan” (pure kindness) cannot be seen, only the individual and God knows it. That is why we are forbidden to judge a person’s faith because we do not know. Even the hypocrisy of a person cannot be judged unless manifested in betrayal behaviour. However, on the measure of the heart, only he and Allah know whether he is hypocritical or truthful. The hypocrite actually has a disease in his heart.

Imam Al-Ghazali says if we are asked who we are then we answer, “I am human. I eat, drink, and sleep“, we just talk about animal spirit or animal passion. Sensing is concrete imagery. Meanwhile, Imam Al-Ghazali combines the three deeper layers of the soul into one into the human spirit or human passion, which essentially longing for God. That is, the stronger the human spirit of a person, the closer and the longer he is to God [6]. On the contrary, the increasingly powerful human sensate mentality, the term popularized by Pitirim Sorokin, will become increasingly greedy and selfish as it is only concerned with the soul and its own body, not too concerned with the phenomenon that occurs. That is what explains the strange behaviours that occur in this digital age.

Specific psychological intervention may be needed to address these psychological problems of the digital era. Among the existing psychotherapy approaches, cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) has been one of the most widely studied approach [5]. CBT refers to a family of interventions whose core principle is that mental illness and psychological problems are caused by cognitive factors. The purpose of CBT is to evaluate, challenge, and modify clients’ dysfunctional thoughts [7]. In CBT, homework assignments and activities outside treatment sessions are emphasized. There are two types of CBT: (1) CBT that focuses on cognitive restructuring as the core treatment feature and (2) CBT wherein cognitive restructuring is important, but there are certain other features that also play a role (e.g., social skills training, relaxation, coping skills) [7].

Researchers have applied disorder-specific CBT programs which focus on a wide range of cognitive and behavioral factors of different types of mental illness [4; 8; 21]. Although disorder-specific CBT manuals differ in their delivery techniques, all of them have the same core principle to treatment. They further noted that the goal of CBT is to reduce symptoms, enhance functioning, and alleviate the illness. The client actively collaborates with the therapist in a problem-solving process to change maladaptive thinking and behavioural patterns. Despite emphasizing cognitive aspects, the strategies of CBT acknowledge physiological, emotional, and behavioural aspects as these aspects also contribute to the maintenance of the illness.

Previous studies have documented the efficacy of CBT. For example, Butler et al.’s [5] findings (N = 16 meta-analyses) indicated that CBT is effective in treating depression, generalized anxiety disorder and other anxiety disorders, and PTSD. Another meta-analytic review showed that CBT produced clinically significant responses for non-comorbid chronic insomnia, and thus is an effective treatment for this disorder [23]. Moreover, many other meta-analytic studies have provided evidence on the efficacy of CBT programs to treat a variety of mental disorders among different populations; such as trauma-focused CBT (TF-CBT) for children and adolescents, CBT for medication-resistant positive symptoms among patients with schizophrenia, CBT for adult anxiety disorders, and CBT for anxiety in youth with autism spectrum disorders [2; 4; 21; 25].

Other findings using a randomized controlled design showed that TF-CBT intervention reduced posttraumatic stress symptoms and psychosocial barriers among war-affected girls [14}. In addition, Jensen et al. [11] examined the effectiveness of trauma-focused CBT (TF-CBT). Their results suggested that TF- CBT is effective in treating traumatized youth in community mental health clinics and possibly in other countries outside the United States. In general, CBT has proven to be an effective treatment for many psychological disorders.

However, despite the enormous research evidence, CBT has its limitations. Gaudiano [9] summarized some of the criticisms of traditional CBT. First, it is often argued that CBT approach is “too mechanistic and fails to address the concerns of the ‘whole’ patient” [9, p. 6]. Second, CBT does not address the neurological factors; how they link to cognitive factors. Third, the mechanisms of action in CBT are still unclear.

Another problem is CBT approaches mainly focus on cognitive restructuring [7]. It does not touch upon the empathy layer and the spiritual layer; the two deepest layers of the human soul. Therefore, we need a new method which addresses each of the layers. Especially, this method should be able to increase a person’s sensitivity to the deepest layer of the soul, that is the spiritual layer which is beyond cognition. This suggests the need for developing cognitive-spiritual intervention.

This sensing culture phenomenon occurs when sensing mentality is shared within a group of people in a society. The soul first dimmed from the deepest because the deepest is the most abstract, supernatural, and difficult to access. Thus, mental illness occurs because of emptiness. The heart becomes “dark” and does not “glow” anymore. Often, we are advised to be grateful to be believers because having faith is not easy, and we should treasure it. Many people whose spirituality is darkened gradually affects the darkening of layers of empathy because they begin to lose sensitivity to the unseen. Empathy, which involves the relationship of one soul to another, is also invisible. As a result of diminishing empathy, interpersonal relationships become verbalistic, with vulgar expressions.

A person who experiences sensing mentality, his empathy will gradually dim, so he does not care what others feel. No empathy does not mean no feeling, sometimes even very emotional, but not empathic because his emotions are only focused on themselves. The existence of empathy allows a person to control emotion because empathy involves connecting with other souls.

This is an illustration of people with sensing mentality. He just likes to do fun, pretend, look for sensations everywhere, often bored, and so forth. This sensing mentality is facilitated in such a way by social media. For example, feel offended by a post in the WhatsApp group and then leave the group. Or feel offended because his status is not liked by his friend and instead feel happy when i-liked by many people. Take self-portraits, look for the best angles, then upload and get excited when people comment positively. These things do not aim other than just for fun and for sensation. The sensing mentality can be owned by anyone, including smart people because it’s easy and instant. The empathic culture has begun to disappear from our society, replaced by an instant culture that is one indicator of sensing culture.

Corruption is one form of sensing culture. The former Indonesian President, Abdurrahman Wahid once assumed that corruptors were corrupt because of his low salary, therefore the salary of civil servants was raised. The corruption was still going on and even increased. This is a false assumption because what the corruptor needs is not money but a sensation. For example, a project leader is corrupt because he loves the sensation of being able to manage an enormous budget. This is an example of the absence of reasoning. Moreover, corruption is still profitable because when they are caught and imprisoned, not all of the money taken is taken back by the state. And they are only sentenced for several years in a comfortable prison. That way, corruption is not something that is frightening but sensational and with a system like this, corruption is not getting solved but it will be more exciting.

Figure 1. The Layers of Human Soul

In a healthy soul, the incoming sensation is processed into reasoning, empathy, then interpreted spiritually, into the verses of Allah. When looking at the poor, there is a feeling of empathy and sees it as an opportunity for charity. In the study of the Qur’an or maqasid, every verse of the Qur’an is always brought into the spiritual layer to be understood. Whether it’s about trees, rain, God’s blessings, God’s flawlessness, God’s Mercy, and so on. Thus, a healthy-minded person permeates whatever he or she receives by sensing as much as possible deep to the spiritual layer.

We must be careful, guard our hearts and souls, purify the soul, so our hearts will be alive and we will always feel close to God. With remembering Allah we are reminded of the spiritual. When we are thrilled with the world’s affairs, we calm down, think, contemplate, and feel comfort because the “dzikr” is the real entertainment. However, people who are accustomed to sensing mentality in times of sadness will seek entertainment with things that are sensing as well, including drugs and liquor. They cure her anxiety by forgetting her, denying her, and laughing a lot. We also need to be careful in joking because it can reduce sensitivity. At first, the usual joke can lead to ridiculing others and ridiculing others is not worth laughing at.

In conclusion, we as Muslims must take care of our soul. Our society has been infected with the crazy times that have been described as a sensing culture. This problem is not caused by social media, but because of the emptiness of the soul that is catalyzed with social media. Social media is just the trigger, the victim actually already has problems. It’s just that initially the problem is mild, but it gets worse because it is pulled into a sensing culture. Sensing people think that entertainment will heal them when they are misleading. Therefore, to treat sensing mentality, we need to strengthen our reasoning. For example, when listening to sensational news we need to process it by reasoning, ”Does this make sense?” Then by processing it using empathy, we will understand who spread the news or who is behind it all. When entering the spiritual layer, the information is constructed with the Qur’an because in the Qur’an everything has been explained. Currently, we are being frightened with news that may be true, but actually not as bad as our fear. ”Do not fear them, they are only demons. Fear is only to God!”, said a verse in the Qur’an.

This study is aimed to test the hypothesis that by strengthening the reasoning, empathy and spiritual dimension of the human soul, the sensing mentality can be reduced. To do so a cognitive-spiritual intervention is conducted.

METHOD

The design of the study is a one-group pre-test post-test design (Shadish, Cook, and Campbell, 2002). The participants of the workshop are 22 professionals, most of them are psychologists and educators.

The workshop is conducted in three phases. The first phase used a cognitive approach. The participants were stimulated with questions around the meaning of freedom and the context around it. The purpose of the first phase is to make the participants realize that freedom is something that they are aware of and how to manage it in a way that it doesn’t provoke problems. This treatment will strengthen the reasoning.

On the second phase, affective approach was carried out. On this phase, some video are shown that illustrate emotionally touching phenomena. The messages shown on the video illustrations are about how vulnerable human is. The video illustration was followed with a group discussion in order to make the participant understand and able to feel the message about human vulnerability. The purpose of this treatment is to stimulate empathy.

On the third phase, the participants were brought into a universal reflection about their position in the universe and the meaning of their existence. On this phase, spiritual approach was implemented. Using documentary video on the universe and citation from the verses of Qur’an concerning the relationship between Allah, human being and the universe, the participants were brought into deep reflection about their personal perception on their existence. This treatment will touch the spiritual layer of the soul.

The procedure of the study is as follows: (1) conduct the pre-test; (2) welcoming and personal introduction; (3) presentation on the purpose of the workshop; (4) discussion on “human freedom”; (5) reflecting on human vulnerability; (6) reflecting on life uncertainty and the important role of hope; (7) reflecting on the relationship between “Allah, the universe, and me”; (8) concluding remarks; (9) administer the post-test.

The measure used for the pre-test and post-test was The Anchor Personality Inventory which was developed based on the theory of anchors [18] The Anchor Personality Inventory consists of 40 items that represent four anchor orientations, i.e. (1) self-orientation; (2) others orientation; (3) material orientation; and (4) virtues orientation, with 10 items for each orientation.

Samples of self-orientation items are: (1) “My success in life is the result of my own hard work”; (2) “For me, happiness is when I feel personal satisfaction”; (3) “I am the only one who can make myself happy”. Samples of others orientation items are (1) “So far my luck is determined by others”; (2) “In order to get better results I need suggestions from my friends”; (3) “It worries me if someday I am going to lose my best friends”. Samples of materials orientation items are (1) “For me, there is no complete happiness without wealth”; (2) “Quality of life is about how sufficient you fulfil your material needs”; (3) “I often imagine that I must be very happy if I have big house and luxury cars”. And samples of virtues orientation items are: (1) “Happiness is not defined by how much we have got but how much we have given”; (2) “I believe that the measure of success is not how much we have accomplished but how sincere we have put our efforts.”; (3) “The meaning of life for me is contribution, not personal satisfaction.”

There are three measures that can be produced by the Anchor Personality Inventory, i.e. (1) spiritual dimension which is measured by the score of virtues orientation subtracted by the score of material orientation; (2) interpersonal dimension which is measured by the reversed absolute score of the difference between others orientation and self-orientation; and (3) the overall anchor stability which is measured by the square root of the multiplication of spiritual dimension and interpersonal dimension.

- Spirituality = Virtues - Materials

- Interpersonal = 5 : ABS(Others-Self)

- Anchor = SQRT (Spirit x Interpersonal)

To test the hypothesis, the mean of post-test was compared with the mean of pre-test with the method of paired sample t-test.

RESULTS

Out of 22 participants, there were 20 participants completed pre-test and post-test data. The means difference between pre-test and post-test for each variable are as follows. For spirituality dimension, the mean of pre-test scores is M=1.517, and the mean of the post-test scores is M=2.166. Therefore the mean difference is 0.649, with t-score = 4.25, p<0.01. For the interpersonal dimension, the mean of the pre-test is M=4.615, and the mean of the post-test is M=4.575. Therefore, the mean difference is -0.04, with t-score = 0.454, p>0.05. For the overall stability of the anchor, the mean of pre-test is M=2.716, and the mean of the post-test scores is M=3.521. Therefore, the mean difference is 0.805, with t-score = 17.370, p<0.01.

Table 1

Pre-test and Post-test differences

Variables | Mean Pre-Test | Mean Post-Test | Mean Differences | N | t |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Spirituality | 1.517 | 2.166 | .649 | 20 | 4.250** |

Interpersonal | 4.615 | 4.575 | -.040 | 20 | .454 |

Stability of Anchor | 2.716 | 3.521 | .805 | 20 | 17.370** |

** p < 0.01

The results of the study support the hypothesis that cognitive-spiritual intervention significantly increased the stability of anchors through the spiritual dimension.

DISCUSSION

The study shows that cognitive-spiritual intervention significantly increased the participants’ stability of anchors. These results support the hypothesis. If we investigate further to the dimensions of anchor stability, it shows that it is the spiritual dimension that was affected by the training process. The interpersonal dimension, on the other hand, remained stable. These results could indicate that the training materials were focused on the spiritual dimension. Another possible explanation is that the participants already have strong interpersonal dimension when they joint the training so that there is no more room for improvement. Considering this it is recommended to replicate the study to participants who have weak interpersonal dimension. This result confirmed the previous study by Riyono [17].

Further study can also investigate whether the stability of anchor correlate to happiness or even success in life. At the end, the cognitive-spiritual intervention is aimed at success and happiness in life. It is also interesting to conduct a comparative study between cognitive-spiritual intervention and conventional interventions. The comparison can be measured for their effect on the stability of anchors or directly to wellbeing and happiness. It would be ideal if a longitudinal study can be conducted to investigate the impact on real success in life.

Conclusion

The cognitive-spiritual intervention which is designed in the form of one-day workshop can increase the spiritual orientation of the participants. This means that the cognitive-spiritual intervention can be used as a form of therapy to cure those who have a sensing mentality in order to regain their spiritual sensitivity of their heart.

Список литературы

1. Al-Bakhi A.Z. Sustenance of The Soul: The Cognitive Behavioral Therapy of Ninth Century Physycian. Badri. M.B. (trans.). London: International Institute of Islamic Thought, 2013.

2. Arrelano M.A., Lyman D.R., Jobe-Shields L., George P., Dougherty R.H., Daniels A. S., Delphin-Rittmon M.E. Trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy for children and adolescents: Assessing the evidence. Psychiatric Services, 2014: 65(5). P. 591–602.

3. Brown B. Rising Strong. London: Vermilion, 2015.

4. Burns A.M., Erickson D.H., & Brenner C.A. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for medication-resistant psychosis: A meta-analytic review. Psychiatric Services, 2014: 65(7). P. 874–880.

5. Butler A.C., Chapman J.E., Forman E.M., & Beck A.T. The empirical status of cognitive-behavioral therapy: A review of meta-analyses. Clinical Psychology Review, 2006: (26). P. 17–31.

6. Ghazali Revival of Religious learnings. Ihya Ulum-id-Din. Transl. by Fazlul-Karim. Karachi. https://archive.org/details/IhyaUlumAlDin (Accessed: 24.10.2019)

7. Cuij pers P., van Straten A., Andersson G., & van Oppen P. Psychotherapy for depression in adults: A meta-analysis of comparative outcome studies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 2008: 76(6). P. 909–922.

8. Foa E.B. Cognitive behavioral therapy of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 2010: 12(2). P. 199–207.

9. Gaudiano, B.A. Cognitive-behavioral therapies: Achievements and challenges. Evidence Based Mental Health, 2008: 11. P. 5–7. doi:10.1136/ebmh.11.5.

10. Ibnu Khaldun. Muqaddimah: An Introduction of History (F. Rosenthal, Trans.). New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1377.

11. Jensen T.K., Holt T., Ormhaug, S.M., Egeland K., Granly L., Hoaas L. C., Wentzel-Larsen, T. A randomized effectiveness study comparing trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy with therapy as usual for youth. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 2013. P. 37–41.

12. Kang, S.-M., Shaver, P. R., Sue, S., Min, K.-H., & Jing, H. Culture-specifi c patterns in the prediction of life satisfaction: roles of emotion, relationship quality, and self-esteem. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 2003: 29(12). P. 1596–1608. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167203255986

13. Leary, M. R. The function of self-esteem in terror management theory and sociometer theory: comment on Pyszczynski et al. Psychological Bulletin, 2004: 130(3). P. 478–828. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.130.3.478

14. O’Callaghan, P., McMullen, J., Shannon, C., Raff erty, H., & Black, A. A randomized controlled trial of trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy for sexually exploited war-affected Congolese girls. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 2013: 52(4). P. 359–369.

15. Poulsen S., Lunn S., Daniel S.I., Folke S., Mathiesen B.B., Katznelson H., & Fairburn C.G. A randomized controlled trial of psychoanalytic psychotherapy for cognitive-behavioral therapy for bulimia nervosa. American Journal of Psychiatry, 2014: 171(1). P. 109–116.

16. Pyszczynski T., Greenberg J., Solomon S., Arndt J., & Schimel J. Why do people need self-esteem? A theoretical and empirical review. Psychological Bulletin, 2004: 130(3). P. 435–68. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.130.3.435

17. Riyono B. “ISLAMIC MOTIVATION TRAINING” (IMT) and its effect on the stability of anchors. ICONIPSY Proceeding, 2015: 1(1). P. 158–163.

18. Riyono, B., Himam, F., & Subandi. In search for anchors the fundamental motivational force in compensating for human vulnerability. Gadjah Mada International Journal of Business, 2012: 14(3). P. 229–252. Retrieved from http://www.scopus. com/inward/record.url?eid=2-s2.0-84872200325&partnerID=40&md5=a45c1cf 5f8aab942e70dfedefe94dce9

19. Seligman. M.E. Learned Optimism. New York: Vintage Books, 2006.

20. Shadish W.R., Cook T.D., and Campbell D.T. Experimental and quasiexperimental designs for generalized causal inference. Boston: Houghton Miffl in Company, 2002.

21. Sorokin P. Contemporary Sociological Theories. New York: Harper & Row, 1928.

22. Stewart R.E., & Chambless D.L. Cognitive–behavioral therapy for adult anxiety disorders in clinical practice: A meta-analysis of effectiveness studies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 2009: 77(4). P. 595–606.

23. Toffl er A. Future shock. New York: Random House, 1970.

24. Trauer J.M., Qian M.Y., Doyle J.S., Rajaratnam W, S. M., & Cunnington, D. Cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic insomnia. Annals of Internal Medicine, 2015: 163(3). P. 191–204. doi:10.7326/M14-2841.

25. Turkington D., Kingdon D., & Weiden P.J. Cognitive behavior therapy for schizophrenia. Journal of Psychiatry, 2006: 163(3). P. 365–373. doi:10.1176/appi. ajp.163.3.365.

26. Ung D., Selles R., Small B.J., & Storch E.A. A systematic review and metaanalysis of cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety in youth with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 2015: 46(4). P. 533–547. doi:10.1007/s10578-014-0494-y.

Об авторе

Б. РийоноИндонезия

Багус Рийоно, доктор психологии, факультет психологии

Президент Международной Ассоциации мусульманских психологов

Рецензия

Для цитирования:

Рийоно Б. Чувственная ментальность и когнитивно-духовная терапевтическая интервенция. Minbar. Islamic Studies. 2019;12(4):1091-1106. https://doi.org/10.31162/2618-9569-2019-12-4-1091-1106

For citation:

Riyono B. Sensing Mentality and the Cognitive-Spiritual Intervention. Minbar. Islamic Studies. 2019;12(4):1091-1106. https://doi.org/10.31162/2618-9569-2019-12-4-1091-1106

JATS XML